This article is my submission for Coder Academy - ISK1002 Industry Skills II Assessment 2: Technical Blog Post & Prototype, and is also cross-posted to adriang.dev.

In my previous life, I worked at a sustainability consultancy where our business model (if I’m being honest) was selling hours. Materiality assessments, carbon accounting, ESG strategy… all packaged in neatly scoped projects billed to clients. It worked. But the deeper I got into the work, the more I noticed a growing tension: sustainability managers are short on time, under-resourced, and increasingly expected to do more with less. And the tools available to help them? Expensive, bloated, or nonexistent.

That tension, and the desire to do something about this problem, stayed with me when I moved into software development. So, for this assignment, I built an MVP version of something I always wished we could build back then: a simple, hosted stakeholder survey tool for materiality assessments. Not a big shiny SaaS product, just a focused, modular frontend that makes it easier for companies to collect meaningful insights from their stakeholders.

The Problem (And Why It’s Worth Solving)

Materiality assessments are a foundational tool in sustainability strategy, used to identify and prioritise the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues that matter most to both a business and its stakeholders. These assessments help organisations distinguish between what’s merely interesting and what is truly material - that is, impactful enough to influence decision-making, risk management, and long-term value creation.

According to AuditBoard (n.d.), materiality assessments act as a compass, guiding reporting and sustainability efforts to where they’re most meaningful. Plana (n.d.) further emphasises their strategic value, noting that when done well, they create alignment between internal priorities and stakeholder expectations.

Despite their importance, the process can be time-consuming, resource-heavy, and the process of running one is often manual and inefficient. Many businesses either:

- Are reliant on expensive consultancy services (Zooid, n.d., KPMG, 2014) to run stakeholder interviews and surveys, placing them out of reach for many sustainability teams, or;

- Download a PDF template, paste it into a Google Form or other questionnaire tool and try to make it work.

Neither approach scales well. The first is costly and slow. The second is brittle and limited. What’s more, many of the existing ESG platforms on the market bundle materiality functionality into broader enterprise tools, which often including carbon accounting, emissions tracking, or ESG disclosure. They’re expensive, complex, and opaque (if the pricing page says “Contact Us,” it’s rarely cheap).

And then you have the consultancies from boutique (Zooid) to Big 4 (KPMG) et al, all offering free templates but ultimately trying to upsell billable services.

No one is building a focused, accessible, standalone tool just for materiality assessments.

So I did.

The Materiality Assessment Tool

This MVP is a frontend-only application built in React that does one thing well: it collects materiality input from stakeholders.

The flow:

1. A stakeholder receives a code from the company wanting their input.

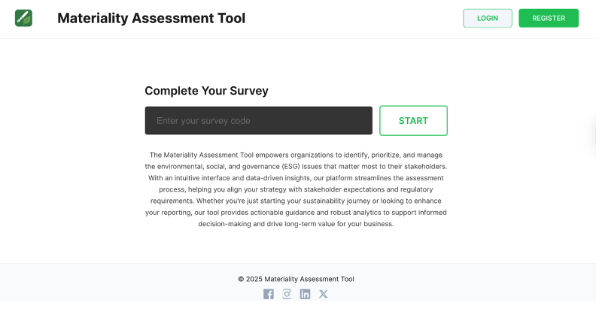

2. The company directs them to a simple landing page, entering their code:

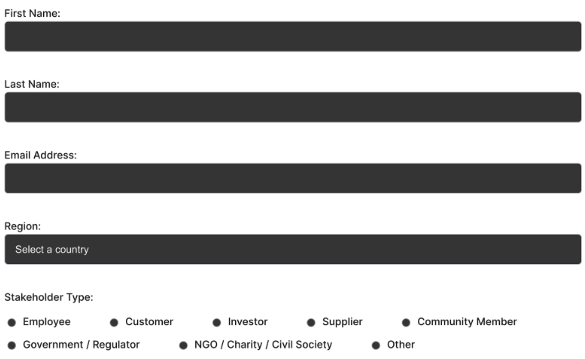

3a. They fill out their details:

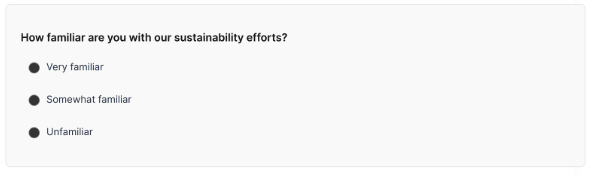

3b. And answer a series of framework-aligned questions:

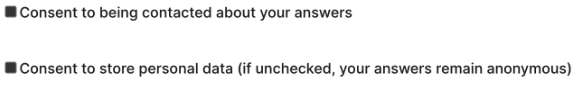

4. Their data is submitted (consensually, and anonymously if required):

No logins, no admin dashboards or analytics (yet). The MVP is deliberately stripped back to a single-screen, frictionless experience that prioritises the stakeholder’s ease of use above all else. The respondent enters a unique code, provides minimal personal information, consents where appropriate, and gets straight into the survey.

This intentional simplicity reflects a key insight from my time in sustainability consulting: if the stakeholder experience is clunky or confusing, participation drops, and the whole materiality process risks falling apart. Strong, reliable data depends on making it easy for people to contribute. Everything else comes after.

Tech Choices

This is a MERN stack app (MongoDB, Express, React, Node), hosted with:

- MongoDB Atlas (for the database)

- Render (for the backend API)

- Netlify (for the frontend, once live)

Why this stack? Honestly: speed. I’ve built a few MERN apps lately, so the setup is fast, the ecosystem is familiar, and I can stand up an MVP in days instead of weeks.

Sure, SQL might be more appropriate down the line (especially for data analysis and reporting) once the tool progresses beyond MVP, however, I didn’t need rapid data queries or relational joins at this stage (Amazon Web Services, n.d.).

The goal was to test the idea, not design the perfect architecture.

Survey Components

From a React standpoint, the frontend uses modular components for each question type within a particular sustainability framework:

- SingleChoiceQuestion

- MatrixQuestion

- RankingQuestion

- TextQuestion

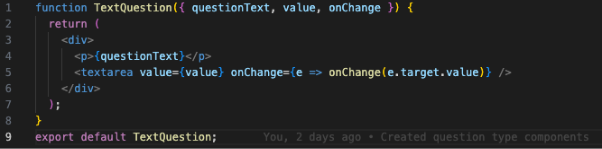

Here is an example of the TextQuestion component (where the respondent is asked for a short text-based answer):

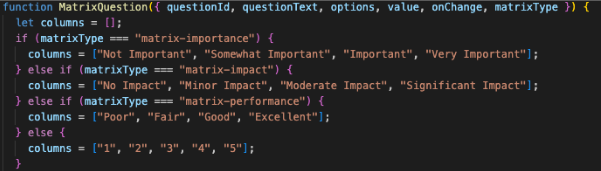

Using modular components allowed me to build the survey form in a way that is both scalable and maintainable. Each question type (whether single choice, multiple choice, matrix, or open text) has its own self-contained logic and styling, making it easier to isolate bugs, adjust behaviour, or add new features without touching unrelated code. This approach also lays the groundwork for future expansion, especially if the tool evolves to support multiple sustainability frameworks or custom question templates.

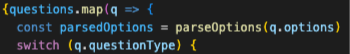

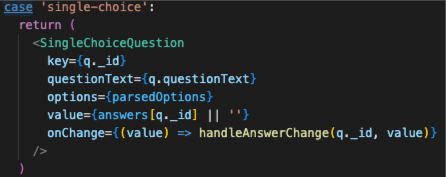

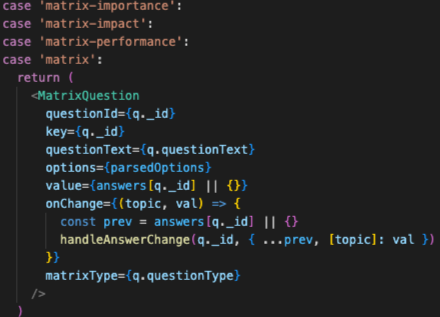

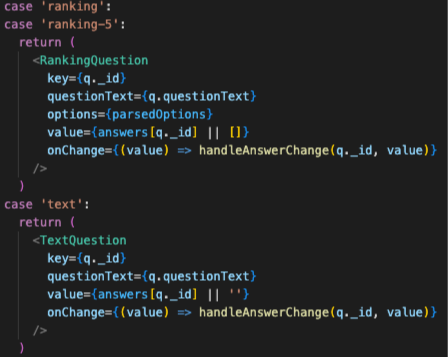

Each component is rendered dynamically based on the question type returned from the API. Here’s the core logic for that:

For each question, it:

- Parses the options with parseOptions.

- Uses a switch statement on q.questionType to determine which component to render.

- Renders the appropriate React component (SingleChoiceQuestion, MatrixQuestion, etc.) with props including questionText, options, value, and an onChange handler that updates the answers state.

Matrix questions required a bit more care. They originally all shared the same questionType, which broke rendering logic. I updated the seed data to use more descriptive types (from “matrix” to “matrix-importance”, “matrix-impact”, etc.), making it easier to select the right component dynamically.

Testing and Feedback Strategy

There’s no formal unit testing setup yet, though the form has been manually tested through every possible interaction. More importantly, I’m preparing to share the tool with a select group of sustainability professionals in my network.

They’ll test the tool from the stakeholder side and answer three key questions:

- Was it easy to use?

- Will it help you collect better materiality data?

- Would you (or your company) pay for a tool like this?

That feedback will determine the project’s future - whether it becomes a commercial micro-SaaS, an open-source tool, or something to license or merge into a larger existing ESG platform.

Ethical and UX Considerations

1. Consent Architecture

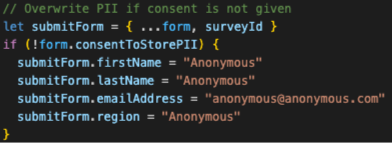

As highlighted earlier, stakeholders must opt in to:

- Be contacted about their answers, and;

- Have their personally identifiable information (PII) stored.

If a user fills in their name and email but declines to have their PII stored, the system overrides their input and replaces it with anonymous placeholders:

It’s a small touch, but it protects the user from their own accidental oversharing. Some thoughtful friction for privacy’s sake.

2. Login-Free Flow

Respondents are often time-poor. We designed the user flow to respect that.

The backend was originally set up with JWT-based auth across all routes. But once the respondent experience was defined, it became clear that requiring login would create unnecessary barriers (Chen, 2020, FullStory, 2021).

Given the data entries are general, non-sensitive inputs, I removed auth from POST /respondent (capturing the respondent’s details) and POST /response (capturing their responses to survey answers), allowing for a one-click, frictionless experience.

What I’d Do Differently

If I were to start this project again, the biggest change would be working on the backend and frontend in parallel. While the backend was technically out of scope for this assignment, it still shaped almost every challenge I encountered while building the frontend, and showed me how unfinished a backend can feel once real users and flows are introduced.

Initially, the backend-frontend relationship followed a waterfall-style approach: finish the backend first, then move on to the frontend. But that linear structure quickly broke down in practice. Once I began building out the frontend and connecting it to actual routes, it became clear that I needed to:

- Seed meaningful data into the database for local development and UI rendering;

- Deploy both the backend (to Render) and the database (MongoDB Atlas) so the frontend could be tested outside of localhost;

- Adjust various API responses so they were more predictable and usable on the frontend; and

- Rethink certain routes (particularly around respondent creation) to align with a frictionless user experience.

All of this pointed to one key learning: backend and frontend development are never as isolated as the planning documents might suggest. Even if responsibilities are split between developers, the two sides of the app need to be shaped around each other, especially when the end goal is a smooth, real-world user flow.

This experience has shifted how I think about scoping MVPs. If the frontend is going to be lean and user-focused, the backend needs to be equally pragmatic. Not over-engineered for hypothetical or future features, but ready to support what’s actually needed at launch.

What This Taught Me

More than anything, this project confirmed something important about how I like to build: I need context. I’m not interested in building software for its own sake, or churning out feature-for-feature clones. What drives me is solving real problems — especially ones I’ve felt firsthand.

This wasn’t just a generic survey app. It was born out of experience, shaped by the hours I’ve spent working in sustainability consulting, helping clients run materiality assessments the slow, expensive way. I’ve lived the friction. I’ve scoped the projects. So building this tool wasn’t a hypothetical exercise - it was a way to address pain points I know inside out.

That sense of context changed how I approached every decision. It made trade-offs clearer. It helped me prioritise UX over theoretical best practices. It reminded me that software doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Rather, it lives or dies by whether it actually makes someone’s life easier.

This project also helped me connect dots between different parts of my background: product thinking, stakeholder empathy, and technical execution. It showed me that when those threads align, building feels purposeful. And that’s how I want to keep building moving forward.

What’s Next?

- Host the frontend, collect & assess feedback from my network

- Pending testing feedback, build the admin dashboard (survey creation, response viewing, data export)

- Possible database migration to PostgreSQL for cleaner analytics

- Decide on monetisation strategy:

- If feedback is strong and users see value: MicroSaaS ($5–20/month for unlimited users)

- If price sensitivity is high: Open-source or license/sell it

This didn’t begin as a technical exercise - it began as a problem I’d lived through and wanted to solve. The assignment gave me the excuse to start. What happens next is up to the people it’s built for.

Published July 2025

References

- Amazon Web Services (n.d.). The difference between MongoDB and PostgreSQL. [online] Available at: https://aws.amazon.com/compare/the-difference-between-mongodb-and-postgresql/ [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- AuditBoard (n.d.). What is a materiality assessment? [online] Available at: https://auditboard.com/blog/materiality-assessment [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- Chen, Nicholas (2020). Friction and UX Design. [online] Medium. Available at: https://nichwch.medium.com/friction-and-ux-design-46cc900d6286 [Accessed 6 Jul. 2025].

- FullStory (2021). User friction: What it is, why it matters, and how to fix it. [online] Available at: https://www.fullstory.com/blog/user-friction/ [Accessed 6 Jul. 2025].

- Greenly (n.d.). What is a Materiality Assessment? [online] Available at: https://greenly.earth/en-gb/blog/company-guide/what-is-a-materiality-assessment [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- Holder, A. (2022). Helping others cite your software. [online] AlexStormwood.com. Available at: https://alexstormwood.com/articles/helpingothersciteyoursoftware/ [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- KPMG (2014). Materiality Assessment: Questions to Ask. [pdf] Available at: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2014/10/materiality-assessment.pdf [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- Novata (n.d.). Company. [online] Available at: https://www.novata.com/company/ [Accessed 6 Jul. 2025].

- Plana (n.d.). Materiality Assessment & Sustainability Strategy. [online] Plana.earth Academy. Available at: https://plana.earth/academy/materiality-assessment-sustainability-strategy [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].

- Zooid (n.d.). Tools – Zooid Sustainability Consulting. [online] Available at: https://www.zooid.com.au/tools/ [Accessed 4 Jul. 2025].